Introduction:

Whether it’s the punishing hours, the daring procedures, or the herculean task of caring for patients, it’s no wonder Neurosurgery has earned a reputation for being one of the toughest fields to thrive in. Some have called it the “Navy SEALS” of medicine, and everyone, at some point or another, has heard someone crack wise over the relative triviality of a task when compared to neurosurgery

(“What’s got ya stumped Jim? It’s not like it’s brain surgery”).

Nevertheless, Neurosurgery has grown into one of the more competitive and well-guarded specialties to enter. To the average first-year medical student such as myself, what’s worth all the trouble? Why do some of the brightest and hardest working applicants line up out the door to dedicate their primes to running the 7-year-long gauntlet that constitutes neurosurgical training? Why set sail for Neurosurgery at all?

I plan on writing three blog posts aimed at answering this question. Each one will be in the form of a vignette. Each as a snapshot of what I’ve experienced in neurosurgery. I hope that through these vignettes, you, the reader, will garner a greater understanding of what makes neurosurgery so appealing for students, and why certain people with specific skills thrive in the field.

Vignette #1:

Early Rise

I rolled out of bed with my scrubs on and immediately checked myself in the mirror to make sure that I did not appear disheveled. Before the rooster’s first crow, I was on the street corner, waiting for the bus. It was 4:45 AM. It was a picturesque Pittsburgh winter morning. There was frost on my breath, and I gazed out at the sky. An inky, turquoise ocean looked back at me,and I felt calm and at peace.

But beneath the surface, more complex feelings swirled. There was excitement, but also turmoil. As the bus turned the corner, I wondered: was I about to embark upon the first waves of my voyage to Neurosurgery? Would the waves be smooth, or rough?

Arriving at Rounds

I arrived at the bus station, and trudged up, ‘cardiac hill,’ the affectionately named 60-degree slope that often leaves medical students huffing and puffing. It was my first day attending neurosurgery trauma rounds. These rounds involve discussions about the management and presentation of the patients who have experienced serious trauma to their nervous systems.

Having been warned that tardiness would ensure the residents would abandon me, I shot through the hospital’s maze of halls. Once I arrived I sat, caught my breath, and chatted with a couple of residents about the holidays and their research.

Typically, these rounds start at 6AM, sharp, and are the first order of business for the neurosurgery residents. For this to be possible, junior residents must arrive at the hospital very early, sometimes even as early as 3:00AM, to check in on every traumapatient. This early arrival is to make sure they have time to gather information before presenting their findings to senior team members.

Trouble on the Horizon

However, I suddenly realized something was wrong. It was 6:02 and the chief residents of the neurosurgery residency program had arrived. However, the junior residents were nowhere to be found. It is customary for the trauma team to present first, before the other services that form the department of neurosurgery. It wasn’t looking good. Instead, trauma presented last.

Although a delay of start, or a departure from the normal order of business may seem like minor setbacks, and may even be minor in other specialties, they are not acceptable in Neurosurgery. Trauma patients in the neuro-ICU are often critically ill. Therefore, the execution of their care must be flawless, and with so much ground to cover, time was precious. They needed to present their findings to the trauma attending, a professor of neurosurgery on faculty in order to make it to the operating rooms on time. The flow of a neurosurgeon’s entire day relies on making every second count. The junior and intern residents scurried in around 6:06 AM. Six minutes late, six minutes gone. The tide was already against them.

The Chief Resident

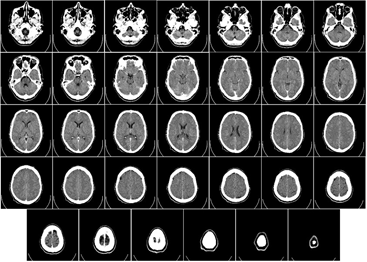

The chief resident, the most senior level trainee started running through the patients fast… like, really fast. As the presenting junior resident would begin a sentence, the chief would finish it, and thunder, ‘NEXT.’ Despite his swift pace, he possessed incredible attention to detail. Every electrolyte that needed to be repleted, and every test in need of ordering spilled from his mind at breakneck pace. Complex CT scans of head traumas were analyzed carefully, yet rapidly. Witnessing the pace required to carry out this challenging and precarious work drew me in, and draws in many other students, too. This is work that gets your blood pumping.

If I could sum up the chief resident in one word, it would be, ‘experienced.’ He knew he was behind, but he also knew exactly how to right the ship because he had probably been in this situation dozens of times before. In fact, in past years he probably was the intern that threw off the schedule. This is another feature of the field that draws students in: nobody is born a neurosurgeon.

The Growth of a Surgeon

Each neurosurgical trainee must embark on their own voyage from frazzled intern to battle-hardened resident, and on this voyage lifelong learning occurs. To this end, I think that neurosurgery attracts people that are devoted to self-improvement and growth. Dr. Ricardo Fontes of Rush University Medical Center recently said that, “the key to medical success as a neurosurgical trainee are the three A’s: availability, affability, and least important, ability.”

In a sense, his words are comforting. Of course, the training will be brutal, requiring dedication, practice, and resilience, but it doesn’t require genius. To me it doesn’t seem like a pass-or-fail examination. It isn’t as if some are worthy and some are not. I take neurosurgical training to be more like the guarantor of an intense experience that forces people to grow. I think that medical students interested in neurosurgery are drawn in by idea that, although they may start as the lowest hand on the ship, through their training, and after years at sea, they will witness their incredible transformation into the captain, capable of handling any challenge.

Visiting the ICU

Following films round, it was time to go see these people in person. I would like to offer warning to anyone who has plans to shadow in neurosurgery: these people don’t so much walk, but rather they jog from point A to B.

I frequently leave New Yorkers in the dust, but as we made our way to the ICU I had to really exert myself to keep up with the residents. There were moments that made me feel slightly disillusioned by it all. It seemed like they were interacting with their documents and lab values more than with their actual patients. These papers are important, but surely these highly qualified physicians didn’t only go into neurosurgery to make sure that potassium was within a certain range… right?

But then something really grabbed me. As the chief discussed the management of a specific patient’s seizures, he glanced over to a patient and noticed she was clearly uncomfortable. He walked over, helped her rearrange her bedding, and asked her if there was anything else that she needed. She responded, ‘thank you, doctor,’ in the sort of way that one says it when they truly mean it.

For a moment, the intense focus that had brought the trauma team back into alignment disappeared and gave way to tenderness. The way chief responded back when he said, ‘of course,’ was as if he was saying it to his own mother. The moment was small and may seem insignificant when read in text, but it was impactful.

Neurosurgery’s Gift

Despite the pace of neurosurgery, the shaky start to the morning, or the complex clinical guidelines the residents rattled off from memory, I could still appreciate that the team really cared about these patients as people. And the patients appreciated this.

Neurosurgery demands that each of its trainees navigate this balancing act. Residents start early and carry tremendous responsibility when coordinating care for their patients. They’re asked to learn and perform intricate operations, some of which approach the zenith of human capability.

Neurosurgery also demands development of leadership skills, and the capacity to overcome setbacks like the one we had experienced on this particular morning. However, beneath all the tasks and work, neurosurgery also asks that no matter how hard the waves may hit, its trainees not lose the guiding principles that brought them to neurosurgery in the first place, which the fact that they care about people and want to help them. Their compassion is both a compass and their north star.

Some of these patients were having the worst day of their life. I think that neurosurgery affords its trainees and practitioners the unique privilege of being able to intervene and be there for people who are in dire straits. Between surgeon and patient, a tight bond can form, and from that bond precious memories are created. For all its tribulations, neurosurgery rewards its practitioners with this incredible gift.